When we think of trailblazing women, figures like Susan B. Anthony often come to mind—women who pushed the boundaries by becoming doctors, lawyers, and suffragists. But another group of women, often forgotten in historical narratives, also pioneered new roles: female pastors and evangelists.

This blog has spent over a decade uncovering the stories of these forgotten women, particularly those in the Free Methodist Church. These women worked in challenging conditions—rural towns, the frontier, and traveling circuits—performing the same duties as their male counterparts. Their ministry was crucial to the success of late 19th-century denominations, yet their stories are largely absent from church history.

The Ongoing Struggle for Recognition

Female evangelists were pivotal in growing the Free Methodist Church, but where are they in the church’s organizational history? Are their stories featured at denominational headquarters or on official websites? Unfortunately, the answer is no. This issue extends beyond one denomination—women’s contributions were not documented in early church histories, making it a laborious task to reintroduce them into the narrative.

To rewrite history accurately, researchers must dig through periodicals, census records, legal documents, and sometimes even locate descendants. There are hundreds of women who dedicated their lives to ministry, yet their stories remain largely untold.

Transcribing History: Female Evangelists in the Free Methodist Church

In the past year, I’ve transcribed annual conference minutes from the Free Methodist Church dating from 1876 to 1912. These records are invaluable for understanding the scope of women’s involvement in ministry. The first documented female evangelists appeared in 1876 in the Susquehanna Conference—two years before the 1878 Book of Discipline recognized female evangelists as equals to their male counterparts.

By documenting these conference minutes, I’ve gathered the names of every woman licensed and appointed to ministry circuits during this period. This has provided a clearer picture of how many women were actively involved in ministry during the late 19th century, especially while B.T. Roberts, the progressive founder of the denomination, was still alive.

Key Findings on Female Evangelists and Ministry Growth

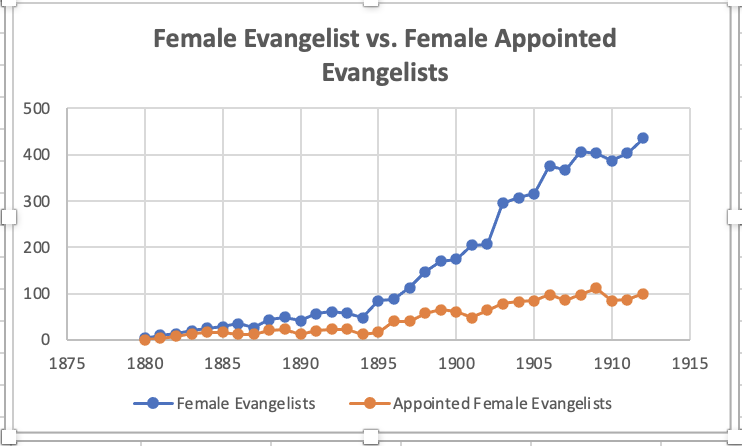

By 1880, there were only three licensed female evangelists, with none officially appointed to circuits. However, by 1912, that number had skyrocketed—435 women were licensed, and 100 were actively appointed to ministry circuits across the U.S. and Canada. Despite the vote against women’s ordination in 1894, women’s involvement in ministry actually increased during this period, defying expectations.

Interestingly, while the number of women licensed as evangelists steadily rose, the number of women appointed to circuits saw only a modest increase. Why? My research suggests this may have been due to societal changes in the Progressive Era, when women became more involved in social causes, including ministry.

Changing Roles in Ministry: From Evangelist to Deaconess

By the early 1900s, more Free Methodist conferences were licensing women, and by 1907, women evangelists could serve as ministerial delegates and pastors. In 1910, they gained the right to be ordained as deaconesses, allowing them to serve in nearly all church leadership roles—except as ordained elders, which limited their access to the highest positions of power within the denomination.

From 1890 to 1912, the number of women licensed as evangelists outpaced men. In 1890, women made up just 2% of licensed evangelists, but by 1910, that figure had soared to 81%. Despite this progress, women were not granted ordination as elders, even though they were performing the same duties as men.

Missed Opportunities for Equality in Church Leadership

Why weren’t women ordained as elders, despite their contributions? It seems the Free Methodist Church missed a critical opportunity in the early 20th century. As the denomination became more structured and bureaucratic, policies were formed without input from women, perpetuating a status quo that excluded them from the highest levels of leadership. This was not necessarily a malicious decision, but rather one born out of complacency—a complacency that stifled progress.

As the 20th century progressed, gendered rhetoric in Christianity, popularized by evangelists like Billy Sunday and Dwight L. Moody, further entrenched the idea that women were not suited for leadership roles in the church. This division between gender roles, both at home and in ministry, remains surprisingly similar to the debates over women’s ordination from over a century ago.

The Legacy of Forgotten Female Pastors

By the mid-20th century, even holiness churches like the Free Methodist Church had lost their feminist roots. Generations of women grew up without role models in public ministry, and many evangelical women never heard a female preacher in their lifetime. This historical distance allowed denominations to forget their ties to early feminist and suffrage movements.

Today, American denominations must ask themselves, “Who have we overlooked?” Every denomination likely has a forgotten group of individuals whose stories need to be written back into history. The narratives of women pastors and evangelists in the Free Methodist Church—and beyond—are an essential part of that history.

[i] Robert Martin, “Billy Sunday ad Christian Manliness,” The Historian 58(4) 1996.

[ii]Donald Dayton, Discovering an Evangelical Heritage (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1976), 98.

[iii] Janette Hassey, No Time for Silence (Minneapolis, MN: Christians for Biblical Equality, 1986), 137-138.