The 1911 Free Methodist General Conference marked a significant step in recognizing women’s roles within the church by allowing women to become ordained deacons at the annual conference level. However, this decision came with the caveat that “this ordination of women shall not be considered a step towards ordination as an elder.”

While I plan to write about all five women who were pivotal during this time, Ada Hall stands out as my favorite. I feel a kindred spirit in her writing and passion for the causes she believed were important enough to fight for.

Ada Hall: A Trailblazer for Women’s Ordination

Prior to her ordination as a deacon, Hall served for ten years in circuits within the Minnesota and Northern Iowa Conferences. She was an outspoken advocate for women’s ordination, publishing an article titled “Forward, Backward, Which?” in the April 25, 1911, issue of The Free Methodist. In this piece, Hall expressed the frustrations of female evangelists who were forced to continually defend the denomination’s stance on women’s ordination to outsiders. Notably, this article was published before the 1911 General Conference, highlighting Hall’s determination to push for change.

Hall’s concerns stemmed from the lack of clarity surrounding the status of women evangelists, which was frustrating. She noted that ordination for women was becoming increasingly common, stating:

“We have been humiliated and ashamed when we have to explain to outside people the position of our church on this question. They always go away disappointed, for they expect better things of us because of our high spiritual standard. As laborers together with God and with one another in the great harvest field, seeing the night so soon cometh, is it not wise that you rather help those women who labor among you, and save them from laboring under the present humiliating hindrances?”

The Quest for Recognition

Hall explained that women did not seek to surpass their male counterparts but rather wanted acknowledgment and a title that reflected their contributions:

“We came from the position of an evangelist-pastor one hour to that of a conference preacher. The next we know not what we are nor to what class we belong. Is not this a subject of more importance than deciding names? If we had but one name and knew what it stood for, we would be thankful. This question will not never down or be settled until the right is reached.”

Hall’s article reveals an ongoing rhetorical trend within the denomination—changing the titles of roles available to women to create the illusion of greater ministerial authority without actually granting it. When women were first licensed as evangelists in 1878, they were simply called “evangelists.” However, as Hall later pointed out, the designation grew more complex, with evangelists being licensed by either a quarterly or an annual conference. The annual conference minutes became filled with titles like “quarterly conference evangelists,” “annual conference evangelists,” or simply “evangelist,” depending on the minutes being referenced.

Complications from Past Rulings

Further complicating matters was the 1907 General Conference ruling, which allowed female evangelists to be appointed as ministerial delegates to quarterly and annual conferences if they had served as local pastors for two consecutive years. By 1907, women could preach and serve as ministerial delegates under certain conditions, but they still could not marry, baptize, or serve Communion.

Hall’s frustration likely fueled her embrace of ordination in any form, as it provided her a way to legitimize her role as a local pastor and granted her the authority to perform baptisms, marriages, and Communion. Hall effectively flipped the script, using titles to elevate herself to the position she was already filling.

The Use of the Title “Rev.”

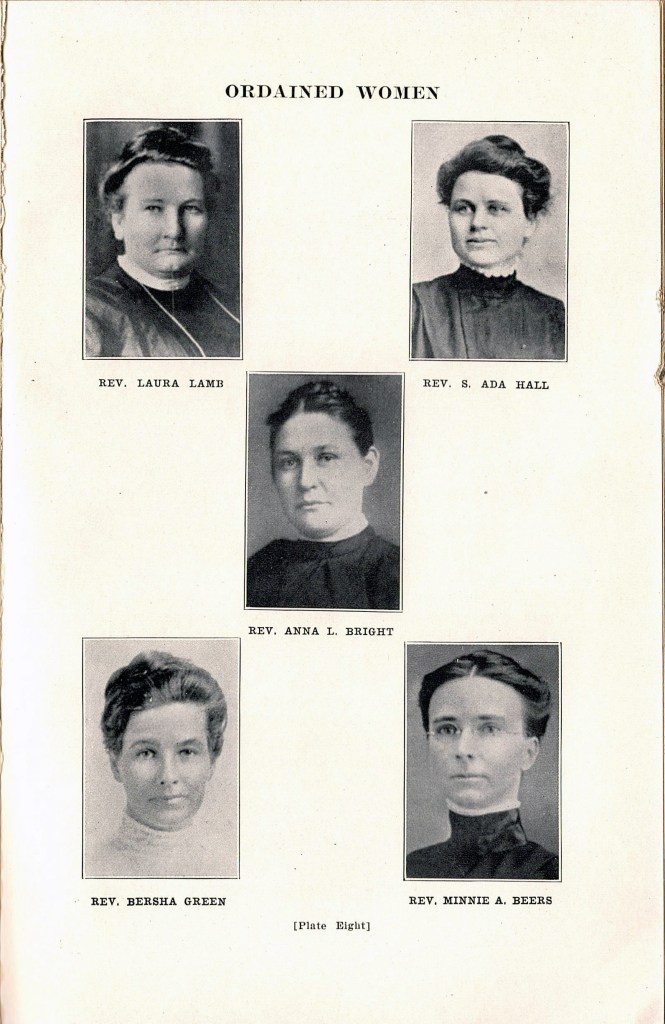

What’s particularly fascinating in studying these women deacons is their adoption of the title “Rev.” after their ordination. When the first women were ordained deacons in 1913, Bishop Burton Jones, a supporter of women preaching, wrote a front-page editorial in The Free Methodist praising the achievements of the first five women ordained. Jones referred to Laura Lamb, Ada Hall, Bersha Green, Anna Bright, and Minnie Beers as “Reverend,” yet there is no indication this was an official title recognized by the denomination, as annual conference appointments continued to refer to women as “Miss” or “Mrs.” Only ordained elders were addressed with the title “Rev.”

Local Perceptions and Church Policy

In addition to Jones’ usage of “Rev.,” local newspapers frequently referred to women deacons as “Rev.” However, this practice did not appear to reflect official church policy. Announcements published in local papers about the following year’s Free Methodist appointments, akin to today’s press releases, did not use the title “Rev.” for women deacons. Instead, these women were also referred to as “Miss” or “Mrs.,” with only ordained elders being called “Rev.”

[i] In the Annual Conference Minutes of the Free Methodist Church of North America the standard reporting practice was to call women evangelists and women deacons “Mrs.” or “Miss” and ordained male elders by “Rev.”

1 The Free Methodist Church Book of Discipline, Free Methodist Publishing House, Chicago, 1907 & 1911.

2 See 1913-1920 Annual Minutes Free Methodist Church of North America. Chicago: Free Methodist Publishing House. What is also interesting is women deacons are listed in the annual conference report as deacons but in the conference rolls that list elders, deacons, evangelists, deaconess, and Sunday School Superintendents they are not included at all.

Thanks for your research and writing on this! The image is a powerful reminder that the recent Southern Baptist Convention-related tweets are wrong when they say ordination of women equals theological liberalism/drift, and you also reveal that it’s always been hard for women pastors to gain acceptance from some people.

Thanks, Jeff- the Southern Baptist tweets use a common argument against women’s ordination. Even in the time period, I research there were Free Methodists who thought women should primarily remain in the home or in caring ministries such as the deaconess order. It definitely doesn’t equal liberalism. Many Christian denominations can trace their success and expansion to countless women who blazed the trail and established church plants! Women in ministry isn’t a new phenomenon 🙂

Just stumbled on this photo in a history of the FMC and found this article when trying to research the women in it. Thank you so much!!!!

No problem- Ada Hall is one of my favorite women. So sassy. I love sharing her story and impact!