This article is from a larger, forthcoming chapter “On the Warpath for God: The Adventures of Pentecost Band Women 1885-1890“ in Spirited Sisters, a forthcoming collection from Pennsylvania State University Press about Holiness and Penecostal women.

In the spring of 1889, in the small town of Camargo, Illinois, a local drama unfolded that would capture the attention of regional newspapers across the Midwest. The catalyst was faith. Nineteen-year-old Nettie Davis and her seventeen-year-old sister Lillian felt a strong call to join the Free Methodist Pentecost Bands, a dynamic, traveling evangelistic movement. They were inspired by the preaching of Sievert Ulness and other members of Band No. 12, who were visiting their town. However, their decision was met with immediate and violent opposition from their father, Samuel Davis. Davis was “furious” and forcibly removed his daughters from a church service. When Band leader Ulness tried to intervene, Davis reportedly “soundly thrashed” him. The following day, Davis physically assaulted other Band members on the streets of Camargo.

Sensationalism and Slander in the Press

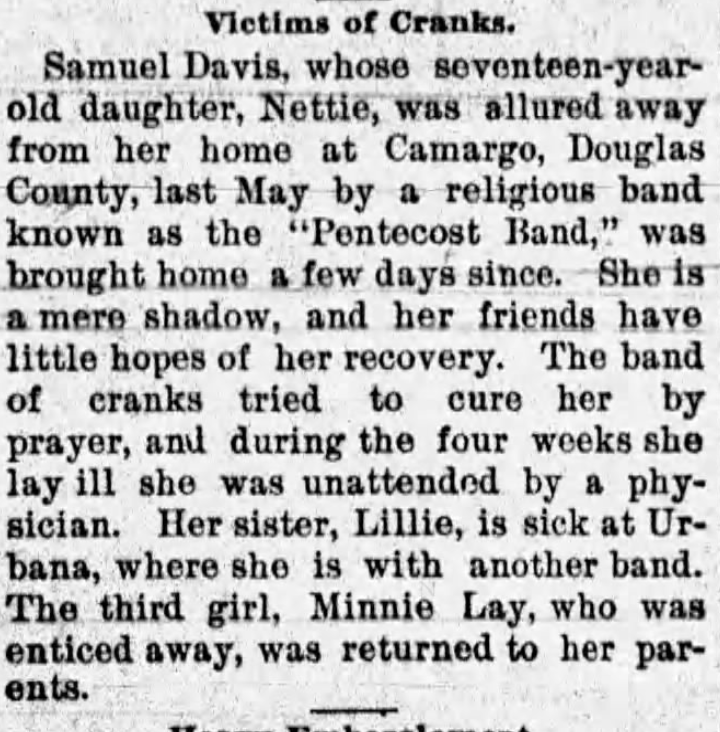

Regional newspapers seized on the story, turning the family dispute into a sensational media circus. The press was highly critical of the Pentecost Bands, often framing them as dangerous outsiders. Headlines and reports frequently used loaded language, calling the Band members “religious lunatics” and even falsely accusing them of being “Mormon missionaries in disguise” who were trying to break up families and steal daughters. The coverage of the Davis family saga perfectly illustrates how the media demonized the movement: The stories heavily focused on the women in the Bands, depicting their unconventional public ministry as “deviant social behavior.” Additionally, Nettie and Lillian’s own voices and wishes were completely ignored. They were not quoted and were instead painted as victims who had been deceived by religious fanatics. Conversely, the media portrayed Samuel Davis as the hero—a desperate father protecting his daughters from a dangerous cult.

The Story that Wouldn’t Die

Despite their father’s extreme opposition, both Nettie and Lillian successfully left home and joined different female-led Bands, continuing their ministry for several years. But the media saga followed them. In July 1889, Nettie’s band was arrested in Tuscola, Illinois, for street preaching. Their subsequent trial was so newsworthy that it was featured in The Chicago Tribune, which repeated the claim that the women were “Mormons.” Nettie was thrust back into the headlines in November 1889 after she fell ill and had to return home. Wire services picked up the story, accusing her Band of refusing her medical treatment. Headlines were dramatic and false: “Brought Home to Die” and “Faith Curers Destroyed Lives of Innocent.” The press again used the story to elevate her father, portraying his decision to take her back as an act of immense forgiveness. The Hillsboro Journal implied that her illness and return were divine judgment.

However, despite numerous stories predicting Nettie’s imminent death, she recovered and returned to the Bands where she continued to minister until her marriage in 1893. Her return and subsequent years in the bands were not reported by the press. Instead, news coverage of the Davis family ended with Nettie near death’s door.

(Note: I have tried to find more on Nettie post 1893 but so far no luck. If any of her descendants come across this post- please reach out!)

Additional Information:

“Should be Tarred and Feathered,” Freeport Daily Bulletin (Freeport, Ill.), June 11, 1889, 3.

Nettie Davis’ involvement is also mentioned by Nelson in his book. Nelson, Life and Labors, 262

“Victims of Cranks,” Effingham Democrat (Effingham, Ill.), 1889, November 27, 1889, 4; “Brought Home to Die: How the Faith Curists Destroyed the Lives of Innocents,” Herald-Dispatch (Decatur, Ill.), November 16, 1889,1 & “Left the Pentecost Band,” Chicago Tribune, November 23, 1889, 7.